There is no shortage of advice these days about how to deal with the “problem behavior” of people who have dementia, many of whom get more resistant as their conditions decline. Many of those urgings seem impossible to follow; some of them too wonky, too time-consuming or too expensive. In fact, the best advice may come from an unexpected source: the tried and true tips offered by family members and friends doubling as caregivers who have come up with creative ways to provide it.

Presented here, a collection of simple ideas divined by those who tried them out — and were able to report the happy results.

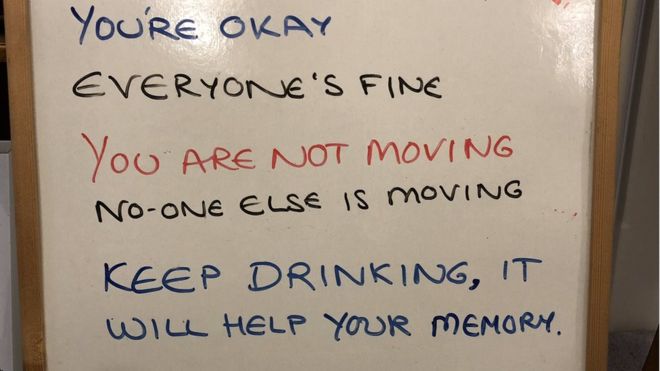

Reassurance on a Whiteboard. A daughter became overwhelmed by the sheer volume of phone calls from her mother who has dementia, constantly seeking reassurance about issues that made her most anxious. Her solution was to write down some simply worded targeted phrases on a whiteboard, visible at her mother’s eye-level.

Those words included:

You’re okay; everyone’s fine. You are not moving; no one else is moving. Keep drinking; it will help your memory. You don’t owe anyone any money. You haven’t upset anyone.

As reported by the BBC, Philip Grimmer, a doctor in the UK saw this whiteboard in a patient’s home while visiting and was impressed enough to send out a tweet about it to a few colleagues. “I’d not seen anything like it before in thousands of house visits,” he said. “It’s caring, reassuring, and sensible.” His tweet quickly went viral, and got tens of thousands of likes. A caregiver living in India saw the tweet and reported he had success in soothing an elderly grandmother who had dementia and thought she was prohibited from using the bathroom, which caused her to become extremely agitated. The message he offered on her whiteboard: “You can use the bathroom whenever you like.”

Revisiting the View. A grandson tells of an outing he helped engineer — memorable on a number of levels: “My dad and I took my grandpa, who has been suffering from dementia for a long time, out for a nature ride, and then to Vancouver. He loves the place. It had been a long time since we took him anywhere. We arrived at night and stayed in a hotel. In the morning, we woke up to the beautiful sea view. ‘Vancouver is a beautiful city,’ grandpa used to say. He was lost in his memories. He said in his time people used to come from far places just to camp there. Some places bring back the memories. He was very happy, and quite surprisingly, he remembered many things from the past.”

Duct Tape for Wanderers. In another tweet, a man shared the family’s idea of using tape on the floor to mark the path for an elderly woman with dementia who frequently got up during the night to use the bathroom — and just as frequently lost her way while going to and from the bedroom.

A Lock on High. After his wife, who had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, wandered away and was lost for 15 hours, a man in Minnesota hit upon the simple solution of installing a deadbolt lock on the front door of the house. The woman is diminutive — 4’10 and getting shorter — and the new lock is just out of her reach. After a few unsuccessful tugs on the front door, she simply gives up trying and alights on another activity. He says he is relieved not to have to intercede by chastising her not to wander off — and that lock has succeeded where expensive wearable tracking devices failed.

Help Unfolding. A sensitively-attuned caregiving grandson reported: “I would give my grandma the same basket of towels to fold — and she would do them so precisely. I kept a laundry basket behind the couch, and we would cycle through the same basket quite a few times. She felt she was helping the household, and it made her feel good and useful, like she was a valuable member of our team.”

Caring Through the Generations. One woman reported that a coddled object not only helped calm her relative who had dementia, it then provided continuing comfort for her survivors after she died. “My great-aunt had a doll she was certain was alive. She repeatedly made sure my aunt would take care of the doll after she passed, which my aunt still does decades later, she said. Luckily, the doll isn’t too fussy and is easy to care for.”

Here to Help. A number of family caregivers said that they got the most positive response from their relatives who had dementia when they said to them: “I really need your help. Can you help with [name a simple task you know they can master easily].”

Talk Less, Smile More. For many people with dementia, changes in the brain make it progressively more difficult to process and understand speech, which can lead to frustration, which can also lead to feeling unsafe or scared. To compensate, their attention to physical cues — smiles, pats, sometimes hugs — becomes more acute. “I noticed when I finally got used to sitting quietly with my husband rather than keep trying to keep a conversation going, he really became more relaxed and less anxious,” said one woman whose mate was in mid state of Alzheimer’s.

Getting to Yes, Please. One woman, a nurse with a lot of personal experience caring for people with dementia, emphasized the need to get some type of agreement from people and to tune into personal histories of those who resist caregiving help. For example, encouraging a person who’s been bucking about personal hygiene to spend time getting obviously messy in a garden or kitchen, or doing it together, might help trigger the idea that a bath or shower is a good next step.

Saved By the Music. Music is a primal soother for many people — and that’s true for a great number of those with dementia. If the person you are caring for becomes agitated or combative, it may help to play some soft music or a favorite song from the past. It can be immediately calming, diverting — and fun.