Updated August 2025

As I’ve said for years, the world is poised on the precipice of what could be called a demographic tsumani. Cogitate on these numbers for a moment:

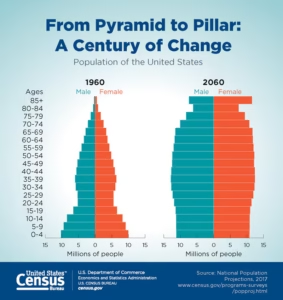

Growth in the proportion of elderly population across several industrialized nations. From http://bit.ly/245d4VJ

Obviously, these numbers have huge implications. I’ve been seeing projections like these looming for years, way back when I started my career in geriatrics in the early ‘00s (pronounced as “ought-oughts,” as an aside). In fact, and more to the point — graphs like the above are one of the reasons I decided to specialize in this kind of work. For a short time, I considered child and family psychology as a specialty. I assumed a growing population would mean more children born, and therefore, a growing base of individuals who would potentially need my help. But graphs like the above really illustrate that the population in the industrialized world isn’t getting younger, it’s getting older.

In 2022, almost 10% of the world’s population had reached or passed the age or 65. Older adults made up a substantial share of the population in some high-income countries, including Japan (30%), Italy (24%), and Finland (23%).The senior share of the world’s population is projected [Kayla: link projected to https://www.visualcapitalist.com/cp/charted-the-worlds-aging-population-1950-to-2100/] to reach 16% in 2050 and 24% in 2100. By 2100, more than 40% of the population in many lower-income countries — including Albania, Kosovo, and China — will be 65 or older.

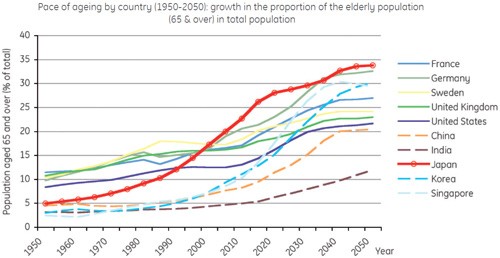

Here’s some more data to illustrate this point, focusing on the US now:

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Notice something about the chart? As time marches on, we’re certainly adding more children to the US population, but not as quickly as we are adding to most age groups of people who are older than 20. As you follow the chart upwards, you note that the largest growth in the US population will occur in people who are between the ages of 30 and 69. Fewer Americans will be born to offset those who are aging into their senior years. In 2060, members of age group 60 and 64 will outnumber people who are younger than age 5.

You can even view this data in the form of animations. For example, study this chart from the Calculated Risk blog (it charts the data from 1900 to 2060). You can see that the shape of the age curve that represents the US population (as well as much of the industrialized world) is flattening. This is an effect that has massive implications for the shape of modern society to come. Everything from how the US government’s Social Security program is funded, the structure of the healthcare system in coming years, our entire US economy in fact will change.

Another striking example for you: In Japan, which is by many measures ahead of the United States in terms of the aging of its population, sales of adult incontinence briefs now outstrips sales of children’s diapers. This is, in part, a stark illustration of the fact that much of Japan’s population is now made up of older adults who require these products in order to maintain basic hygiene and independence in their later years. But this example also illustrates the degree to which the population boom in older adults has resulted in the mainstreaming of products that were once considered “taboo.” Incontinence products are now very visibly seen on the shelves at my local Costco, placed very near the kiosk where they sell hearing aids (likely not a coincidence of any kind).

So, as a long-term care psychologist, the question I have is: how do these trends impact the demand for nursing homes? The easy answer is — “duh, that’s obvious Dr. Lane” — as the proportion of the US population that’s over the age of 70 grows (and it will grow precipitously over the coming years); the demand for nursing homes will rise rapidly, and risk overwhelming our system of long-term care and elder care, at least according to some.

If current disability trends hold (that is, adults in the US age 65 and older spend between two-thirds to three-quarters of their post-65 years free of disability), or get worse; and if the current methods for funding long-term care continue on into the future (primarily Medicaid), we will be absolutely swamped by the amount of money we will need to spend (and be taxed for) in order to fund such care. Unfortunately, unpopular cuts in the Medicaid budget in 2025 will only hasten the funding crisis for nursing home care.

But not so fast, says James Knickman and Emily Snell, at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. In their excellent article The 2030 Problem: Caring for Aging Baby Boomers, Knickman and Snell paint a more optimistic portrait of the future.

It’s Not All Bad

First off, projections about the US economy tend to be mired in a knee-jerk fashion, in what cognitive psychologists might call the hindsight bias. In other words, when things are going well, we expect such trends to continue in the future. Likewise, when things are going poorly, we expect the same.

Obviously, we don’t know what the US economy will do over the next 20 to 30 years or more. Another pandemic may come along that inhibits the economy’s growth. The effect of tariff increases and massive tax reductions for the wealthiest Americans is still unknown. We may see healthy growth like we saw in the 1980s (4-5% growth), which would actually result in declining overall expenditures on long-term care as a percentage of GDP.

Second, we might see the Medicaid-dominated system of financing long-term care, which is inefficient, expensive, and provides all sorts of negative incentives for economization of care amongst those who need it, get supplanted with more nimble, efficient, market-driven alternatives. (Hey, you never know.) The market for long-term care insurance, which many agree has seen little growth at best and has been highly dysfunctional at its worst, might actually take off. Or, perhaps a viable system of nationally-funded long-term care insurance might finally take shape?

Third, a lot of prognosticators and thinkers fret and worry about the high ‘dependency ratio’ posed by the aging baby boomer population. In the 1950s, there were an average of seven working-age adults for every elderly individual. Today, that number has dropped to three, and it’s projected that by 2050 the number will drop to 2.5. While this will no doubt play havoc with the pyramidal structuring of the Social Security system (as current workers pay for the benefits of current retirees), authors Knickman and Snell point out that this is not much different than the dependency ratios that existed when the baby boomers were children (and also required care). Progress and the economy didn’t stop when the baby boomers were dependent children, and it likely won’t stop when they become dependent older adults as well.

Fourth, who says that long-term care (e.g., skilled nursing care) is the only way to care for older adults? Baby boomers seem to have a lot more going for them than their older counterparts (for example, the majority of seniors in the US – Korean War and WWII-era individuals, the “Greatest Generation”). While a oldest seniors living in nursing homes currently may have had a rough start in life, perhaps suffering prenatal malnutrition, poor access to education, or other privations, the Baby Boom generation had a much better shot. In this group, educational attainment is higher (which tends to be associated with lowered disability status), access to prenatal and early childhood resources has been better (better nutrition, medical care, etc.), they smoke less, and the Baby Boom generation really does seem to understand that it’s important to be physically active in later years.

Finally, medical research into a number of illnesses that plague and disable the elderly (such as dementia) continues apace, and again, there could be some medical advances on the horizon that spell great things for the future of older adults living independently well into their later years.

However, there’s still a problem. A big one.

The One Health Problem to Beat Them All

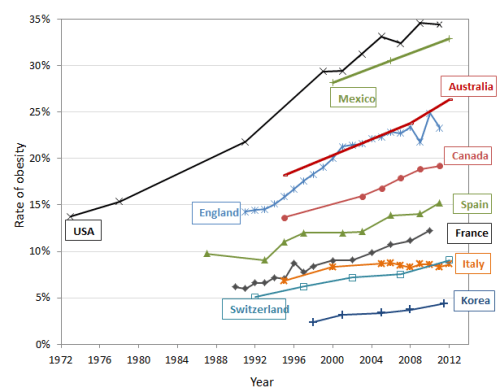

One final graph for you, and in my opinion, one that might really might lend some ammunition to the more pessimistic of takes:

Obesity Trends in the Industrialized World (From OECD)

As the graph demonstrates, the United States leads the world in obesity trends. The problem affects all age groups, although seniors tend to be less obese than Americans who are between the ages of 40 and 59, as this data from 2023 shows:

Source: CDC

While I do tend to believe that it’s always better to be physically active than not, and exercise is important, I do not tend to believe there is such a thing as being “fit and fat.” I think it’s a dangerous myth that it’s better to be a physically active obese individual than it is to be of normal weight and otherwise sedentary. Recent large-scale metanalytic research, as well as research looking at over a million Swedish men, tends to support my position.

So what does this mean? Personally, I think the United States is in a lot of trouble. I don’t have a lot of faith in the long-term economic sustainability of the Medicaid-driven system of long-term care financing. I also am extremely pessimistic about the obesity trends sketched out above — we’re reaching serious critical mass in terms of the obesity epidemic, and despite the other improvements in health markers that have been achieved by the Baby Boom generation, they are, in my opinion, on track to be suffering disability rates in excess of previous generations, and have it be driven entirely by health-related issues.

On the other hand, I tend to think there’s a lot to say for American ingenuity and creativity. Anyone who has followed my personal blog knows that I’m a big fan of innovation and technology. Maybe, just maybe, the US will finally get a handle on its obesity problem, and maybe, just maybe, we can continue to innovate and find new ways to provide care for the older adults who need it. And who knows, maybe the US economy’s best days are ahead, and not behind us. You never know….

(This article was updated August 2025.)